The Evils

Contemporary life in America, while full of material blessings, is plagued by emotional and spiritual poverty, mental health issues, and loss of felt community. Among the chief contributing factors to these plagues is a loss of several kinds of meaningful connection.

- to worthy purposes

- to nature and food

- to local community

- to our bodies and the material world

Contemporary work is marked by a shallowness of purpose: we work for employers whose goal is to make money and in return they give us money. That’s it. Very often, it is not even imagined by either party to this transaction that a higher state of things is possible. Furthermore, the extreme division of labor that has taken place since industrialization means that our work is often so specialized and narrow as to be almost entirely disconnected from the rest of our lives and our larger ideals. Thus, not only the purpose of our work but also its content lacks the ability to connect us to meanings worthy of a life’s devotion: the purpose is money; the content is a super-specialized function so narrow and obscure as to be spiritually impoverished. Our careers–for those who are fortunate enough to have a career rather than a mere job or unemployment–most often lack any sense of vocation.

The complexity of contemporary economics and social life also obscures certain realities and involves us in moral compromise. We do not know where our food comes from and therefore we tend to forget that our relationship with nature is one of utter reliance and also of stewardship. We do not know how most of our belongings came to the store shelves where they are offered for our consumption and therefore we have no idea what was the cost of their production to the environment or to our fellow humans, nor do the items purchased at Walmart carry any meaning for us beyond their functions–no sense that they are the fruit of skill and hope, nor of exploitation, as the case may be.

At our stores, we wield our dollars to reward the manufacturers and producers of the goods we select for purchase, whose business practices we know nothing about. But we are collectively beginning to realize that the rigors of competition and the necessity of maximizing profits can often make morality an unaffordable luxury. Nor need any particular individual compromise their private moralities in any appreciable degree: the various processes that implicate a business as a whole in evil can readily be subdivided and allocated such that everyone just does their little job and the business thrives. Shareholders hold executives accountable for pursuing profits; executives dictate the goals and quotas for the developers and managers accordingly; the developers and managers generate protocols for the workers; the workers carry out their protocols; and the marketing department lines up customers. The compliance department ensures legality, but no department evaluates morality: compliance with laws is quite burdensome enough already. Yet laws can never adequately replace morality: maintaining the decency of a global economy exceeds the capacity of law by far more than inculcating a general love of Shakespeare exceeds the capacity of the public school system.

Even aside from the corrupt and blood-spotted nature of the world of money, there is something inherently paltry and mean in the attempt to extract as much money as possible from our brothers and sisters who are our customers while sharing as little as possible with our brothers and sisters who are our employees. Even where the world of money is not extremely ugly, its core and engine is self-interest, whose smog means that the no corner of its domain is altogether lovely. Any sensitive soul must surely feel the draw of purer air to places beyond the domain of money, where money exists as an expatriate, subject to laws kinder than those of profit.

The methods of contemporary agriculture are industrial. They aim, with impressive success, at controlling and harnessing nature for profit. Science and economic calculation drive the tractor, and any lingering sense of awe, indebtedness, or filial responsibility towards the land must take a back seat. We can hardly expect that the responsibility of a business to safeguard its assets long enough for business purposes will be an adequate substitute for this sense in the long run.

Industrial agriculture renders economically nonviable most farming operations on the scale that has constituted the livelihood of most of our ancestors throughout history (a few acres). To some extent, farmers must go big or leave home. The luxuries of the city beckon the farmer’s children, and rural America shrinks.

What Marx exaggeratedly attributed to the bourgeoisie in the 19th century has, in the 21st, almost become the dominant reality such that it could be more accurately attributed to the “market” today: “It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. . . . [It] has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.”

Since Marx wrote, physicians have begun calculating their services in wRVUs, and attorneys now sum their daily, weekly, monthly, and annual billable hours: the smallest unit by which time is converted to money has become for many in the professions the dominating source of motivation in the daily rigamarole of their careers.

Our neighborhoods provide proximity to others but little community. The book “Bowling Alone” was published in 2000, and we have advanced considerably on the same trajectory since then. Virtual communities have propagated, but for the most part they only increase alienation and loneliness, while at the same time generating echo chambers and polarization. People have their co-workers, their neighbors, and sometimes their churches and other civic organizations. With their co-workers they work; with their neighbors they live; with their fellow members they might share their lives and their souls somewhat more holistically, but only for a few hours a week. With nobody outside their immediate household could they even imagine sharing their lives completely–and the demands of their various shallow communities of work and play and service mean that no complete sharing of their lives is possible even within the nuclear family, which gathers hopefully for one meal a day. This has been the trajectory of society ever since the industrial revolution made the individual the basic economic unit instead of the family and the factory the main site of production instead of the farm.

Ecology is an academic or a political concept: rarely in any other context is it brought to the consciousness of those living in the ecological islands of cities and suburbs. Even physicality itself is becoming obscure for those who dwell too much in the virtual worlds that have propagated during this century: gaming addicts are becoming isolated even from their own bodies, to say nothing of the natural spaces that surround and support their bodies.

The diminishment of consensus about what is moral in various matters from sexuality and family life to substance use and entertainment contributes to a psychology of unmoored individualism and uninhibited choice, where options are many but the value systems by which alone choices can be judged good or bad are so impoverished, especially for the young, as to render most choices equally meaningless.

The net result of these evils is that people are experiencing less and less connection to various meanings. I do not know whether it it true, as I have heard, that our food is becoming less nutritious as it becomes ever more scientifically manipulated for market optimization, but I do know that our experiences are becoming less spiritually fulfilling as these evils leach from our lives our connection to our natural and social environments and to any higher purpose.

A Possible Partial Solution

Imagine a small village of like-minded individuals who have voluntarily opted to partially withdraw from the vast global market of production and consumption and to live in a simpler, slower, less efficient, more difficult, more fulfilling manner by attempting to generate most of their own food and power from their own land in a sustainable manner as a community. This is not a low-tech community; it is high-tech but it subordinates technology to its purposes and principles. Solar panels or geothermal technology power its lightbulbs and ovens and maybe even its tractor, but there are no gaming systems to power. Members may listen to audiobooks while they work, but they do not hop onto ten different social media platforms during breaks.

Among the members of this community are physicians, scientists, teachers, attorneys, salesmen, engineers, and tradesmen who may still work part time at their normal jobs to earn the relatively little money they require. Economic stability is a precondition of membership because it is a precondition of a voluntarily inefficient economic lifestyle. The community participates in the life of the broader society. It is not isolated, secretive, or closed. But it is close-knit, and it is mostly self-sufficient–although its members are known to occasionally visit the grocery store for items that are too difficult to produce on their own land.

Part-time work aside, they each have their community jobs as well. Within this small-scale economic system, there is some degree of specialization of labor, but a much smaller degree than exists in the global economy. One is in charge of maintaining a sufficient flock of chickens to provide all the eggs the community will need and a portion of the fertilizer for their crops; one raises pigs and turkeys for meat; another is in charge of enriching the soil biome through composting and waste management. One family cultivates a rotating acre of potatoes; other families cultivate the three sisters (corn, beans, and squash). Each member of the community works with their hands every day for its benefit. Harvest time involves long sweaty days, shoulder to shoulder, gathering and processing the community’s food and storing it for the winter. Each house is attached to a sizable greenhouse to enable some independence from the local climate and perpetual fresh produce, and they consult together about what herbs and crops should be grown in each of the greenhouses to meet all the needs and many of the wants of the community. Every evening (or perhaps just two or three a week) witnesses a communal dinner followed by singing and music or games or occasionally a movie or a book discussion. No member of the community is required to be present for each such event, but most want to be, and all are expected to be present often.

While a desire for the success of their economic and social experiment unites them at an ideological level, they are of various faiths. They share some but not all political and philosophical opinions. But most of them believe in some higher power and they communally invoke its aid and give thanks for the bounty of their corner of a bountiful earth before every meal and before the meetings in which decisions affecting the community are made.

They have their various projects by which they aim to contribute to society at large, and they help each other in these projects as time and inclination permits even as they push along the communal project that binds them to their land and to each other.

When disagreements arise, an agreed-upon conflict-resolution process rarely fails to render a decision while quickly restoring good relations between neighbors (who are, after all, present in part because they are eager to be on good relations with their neighbors).

In this community, the experience of connectedness and the sense of purpose and vocation that is increasingly absent from mainstream society is cultivated as carefully and lovingly as the gardens and fields.

The Possible Partial Solution And Religion

To be clear, all humans–not just those in an intentional community such as I have described–are children as well as caretakers of the earth, brothers and sisters to each other, and bondservants to whatever highest purpose calls upon them in any given moment. But the economic and social systems in which we maintain ourselves make a dramatic difference in our ability to feel ourselves as such. The village I have attempted to imagine is one in which it is as feasible as possible, prior to the millennium, to stand hand in hand on the soil authentically–where the earth and the people might rejoice together, and heaven smile.

I recently read a book that I greatly appreciated, entitled Called to Community. It compiles essays related to Christian intentional communities, largely by individuals who have felt called to live in communities that attempt to restore something like the communal practices of the earliest Christian church in Jerusalem, where the members voluntarily laid down all their money at Peter’s feet and lived together caring for each other and celebrating the resurrection of the Lord of love and all that His resurrection portends. For some of them, living in a religious intentional community was an expression of God’s Kingdom on the earth.

Without denigrating their experiences or their understandings, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints such as myself cannot entirely accept their vision, because there is no Saint Peter today requesting the bestowal of all our property. There is a Saint Peter figure, to be sure – the living prophet – but the early saints of our dispensation in the days of Joseph Smith tried a throughgoing communal economy as a religious law, and it failed due to human frailty. It seems likely that the same fate befell the early church even in the first generation, for there is ample evidence of private property within the church in the later epistles.

For LDS, at least, the combination of tithing, fast offerings, ministering to each other, and church welfare are what replaced the attempt to live fully the law of consecration as a community. We tried with more success to gather to the Salt Lake Valley or wherever else Brigham Young directed, and now we gather to our Stake Centers and recite the adage that we are to be in the world but not of the world.

To be sure, the decision to settle for partially mitigating the bad effects of full membership in the mainstream economy was a great loss, as attested by the initial failed attempt to avoid doing so. The costs of human frailty are severe. If God’s patience were not inexhaustible, he would surely have given up on us centuries ago.

But for now, any experiment in alternative economic systems will, for LDS people, be totally separate from membership in the Kingdom of God on the earth. It is part of our religion to do good; but an economic/ecological/social experiment is one among many ways of doing good, most of which are not conditions of membership.

D&C 58:26 For behold, it is not meet that I should command in all things; for he that is compelled in all things, the same is a slothful and not a wise servant; wherefore he receiveth no reward. 27 Verily I say, men should be anxiously engaged in a good cause, and do many things of their own free will, and bring to pass much righteousness[.]

Next Steps

Could this vision of a mostly self-sufficient, sustainable, harmonious community actually be achieved? It seems audacious to attempt–but surely that’s how every big change looks to the risk-averse modern consumer living in a climate-controlled house with a steady income. But such people have often been led from walled security into the desert, from the days before monasteries to the present. And many are feeling a similar pull today. “Intentional communities” are cropping up left and right, as are alternative agricultural practices. The Amish attest to the possibility of a dramatically different lifestyle and economic system being sustainable and fulfilling, while existing alongside and remaining partly separate from our society’s mainstream economy. Perhaps somewhere this vision is already fully realized. If so, please tell me where. I would like to visit. If not, doesn’t it seem worth the attempt to realize it as fully as possible?

In the meanwhile (for it will take years to organize the attempt), everyone can take baby steps. We can:

- foster engagement in worthy purposes in any number of ways–by, for example, keeping a journal or a blog or accepting a position in a church or a charity.

- foster connection to nature and food in any number of ways–by, for example, planting and eating from a garden for at least a small part of our diets.

- foster belonging within local communities in any number of ways–by, for example, participating in local government or inviting neighbors for dinner.

- foster connection to our bodies and the material world in any number of ways–by, for example, practicing meditation and minimizing social media participation.

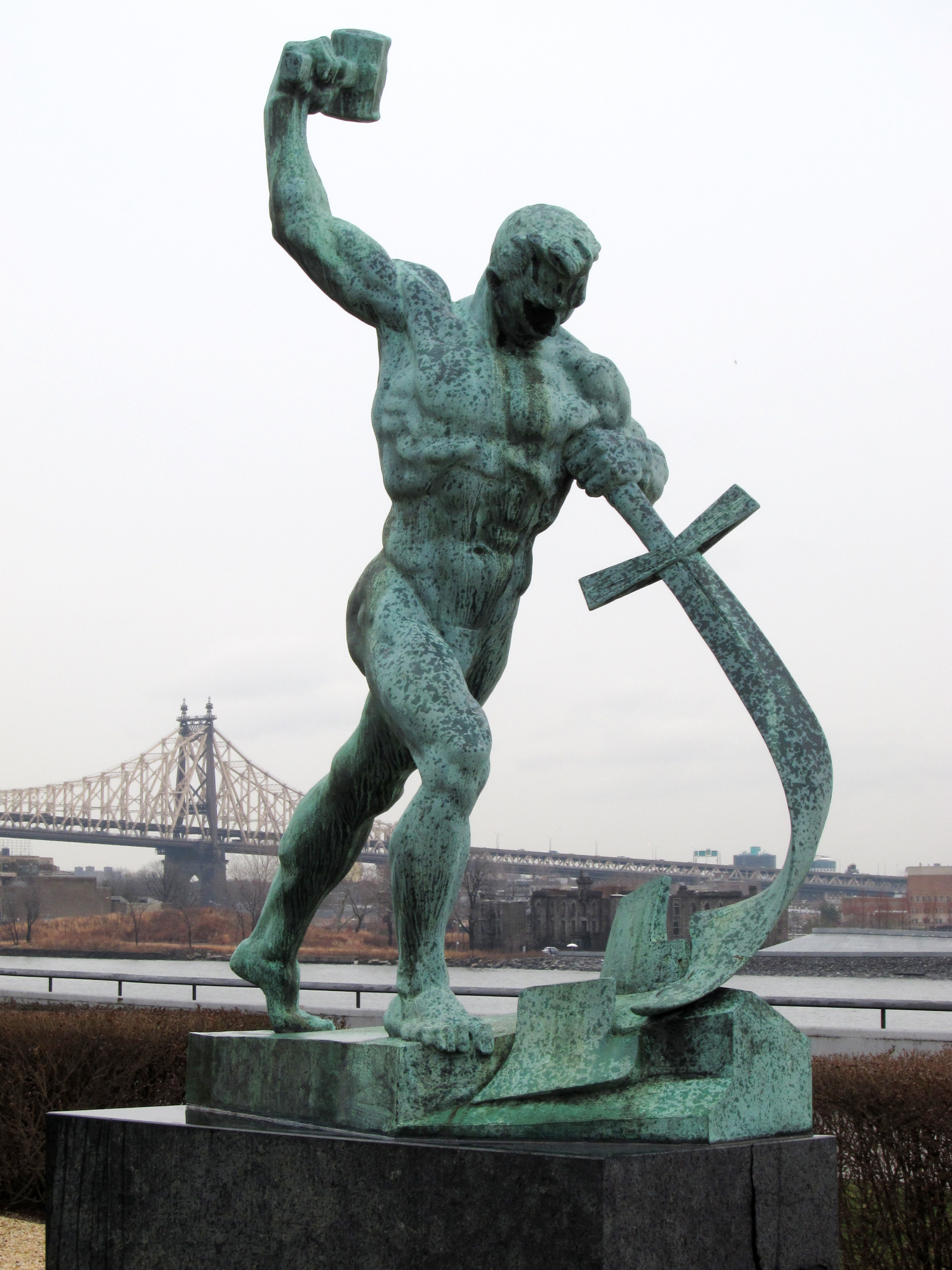

Baby steps are good. But part of the virtue of diligence involves looking for ways to better accomplish the work before us. We should be pleased and grateful, but not satisfied, with each step forward, always looking for ways to take bigger steps. We may be satisfied only with personal and societal perfection. Until that is attained, the last stanzas of Blake’s poem “Jerusalem” beautifully capture the eager aspiration that is our heritage as humans, as Americans, as Christians. Our localities may be substituted for Blake’s “England”; but my envisioned intentional community may not be substituted for “Jerusalem”–it is only one of many possible steps closer to the ideal represented by that term.

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my Arrows of Desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire.

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant Land.

https://ldsanswers.org/what-can-we-learn-from-joseph-smiths-patriarchal-blessings/ Hey! Lovely read, thank you! Have you heard of this faithful LDS family and their website? Hannah Stoddard her siblings and community are the closest thing I have found. They have a permaculture garden in Sanpete County. I got to visit a couple years ago. There stuff is revolutionary. They strive to raise the bar in all areas of life.

Jessica, I had not heard of them. I am interested in permaculture, though. Thanks for reading and commenting!