I recently read Jonathan Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided By Politics and Religion. It is worth reading, but it was a very mixed emotional experience for me. Politically, it was interesting, insightful, and personally affirming, while philosophically it was interesting, insightful, and personally aggravating.

The basis of the book is that Haidt has done extensive research on the differing moral intuitions of conservatives and liberals. (He claims, and I agree, that morality is usually intuited rather than arrived at through rational judgment.) His research confirms that there are broadly two different sets of moralities–not radically different, by any means, but different in emphasis. He claims there are at least six different types of moral intuitions: intuitions relating to care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, sanctity/degradation, and liberty/oppression. He claims that conservatives have much stronger responses in the authority/subversion, sanctity/degradation, and loyalty/betrayal categories, while liberals tend to focus semi-exclusively on the care/harm and fairness/cheating categories. These differences in moral intuition are part of what account for the difficulty of political and religious dialogue. For example, perceived subversion of the institution of marriage and the degradation of the sanctity of human life are highly emotional issues for conservatives, while these tend to barely register as moral issues for liberals, except insofar as the issues also overlap with care/harm or fairness/cheating.

This analysis of the categories of moral intuitions is perhaps the book’s most significant contribution, but where it becomes highly affirming for a social conservative like myself is where Haidt describes becoming sensitized to the sanctity/degradation and authority/subversion intuitions and recognizing their validity, thanks largely to his studies in India about Indian morality. He is and always has been a self-identified liberal, though he has shifted towards the center, so he is essentially admitting, “We liberals have some moral blindspots.” He goes on to also describe his further recognition that writers like Edmund Burke and Adam Smith–classic conservative thinkers–have legitimate points about the value of traditions and social institutions, including religion. He argues that religion and other institutions and traditions have the capacity to foster social capital–by which he means communities with high levels of belonging, trust, and cooperation.

These elements of the book were highly gratifying to read, and I, for one, am persuaded that Haidt is basically right in what he has to say as I have described it so far. But where the book was troubling to me–and even, if I am honest, quite disturbing–is the evolutionary explanation for morality that is a core part of the book’s message. This is disturbing precisely because, after his explanation, it seems utterly plausible—and yet, if true, it cuts the very heart out of morality.

Evolutionary theory is elegant in its simplicity and profound in its explanatory power. While it does not explain how the pre-biological conditions of life arose, it provides a bridge from the earliest forms of life through all gradations of complexity to the human. The complexity and diversity of life are accounted for, more or less adequately, without reference to any extrinsic power or purpose. I am not sure that the presence of life is adequately accounted for. But, if we accept that the random interactions of matter in motion could eventually, and purely by chance, generate, at some location in the immensity of space, a self-replicating organism with DNA in a sufficiently stable environment, then evolutionary theory can take us the rest of the way to a purely materialistic account of all biological life that we observe, including our own.

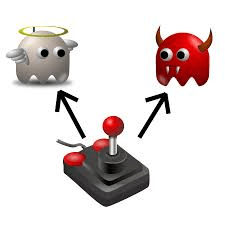

It is threatening enough to a humanistic sensibility, to say nothing of a Christian sensibility, for evolutionary theory to purport to fully explain, without remainder, our biological lives, but I had never before considered at any length the possibility that it might provide a similarly comprehensive explanation of our moral lives. Let us take sexuality as a fruitful point of discussion–fruitful because it is of such fundamental interest to evolutionary theory as well as to morality. Humanism and Christianity alike take cognizance of sexual urges and seek to place them within a meaningful framework that includes rules and higher and lower purposes. But evolutionary theory really explains the urges, while Humanism and Christianity can only take notice of them, or perhaps offer a vague and general explanation, such as “God made us this way” or “The world must be peopled!” The same is true of most of the particular features (or “adaptations”) that our bodies manifest: evolution explains them, while Humanism and Christianity can only take notice of them. This, as I said, is quite disturbing enough, without the blind, unthinking machine of evolution, void of purpose, also accounting for the rules and the meaning that we think we see. I write “that we think we see,” because of course if the perception of rules and meaning is merely the blind production of matter in motion, given direction by the purposeless stream of evolution, then the rules and meaning are mere perceptions—illusions, in other words, because we incorrectly see them as “over us,” when they are really just within us in the same way as the sexual urges they purport to be authorized to govern–and, indeed, the rules and meaning are on just the same level as the urges in terms of value: the “objective” value of each is null. Because, of course, evolution–which is posited as the sole source of directionality in the biological world–does not recognize any value whatsoever. It does not even attribute value to survival and reproduction, but rather adopts these accidentally as its engine and propeller. Therefore, pro-reproductive behavior is not viewed as “good” at all by the theory, but only as a materially determined fact. Pool balls knock into each other and mammals knock up each other–same same. Acceptance of this theory therefore banishes value irrevocably to the quixotic realm of adaptive illusion.

Another way to put it is that if matter in motion is really all that there is (i.e., if crude materialism is true), then any sense of “higher” or “lower,” or “good” or “bad,” along with the mind and consciousness itself, is really mere subjective appearance arising solely from the self-referential firings of synapses in the brain. Scrooge famously said of Marley, “there’s more of gravy than of grave about you,” and, if materialism were true, we would have to similarly say of morality that it has more of the electrical than of the ethical. Nothing is above the brain if everything is within the brain.

But cannot morality simply be redefined as a matter of culturally conditioned perception rather than any sort of capital “T” Truth? Of course it can be defined in this way, but to do so is to forego any claim to the validity of any moral judgment as applied to self or others. If morality is just a matter of perception with no reality “above” the perceiving subject and no priority over other perceptions, then there is no legitimate basis to say that any so-called “bad” behavior is wrong, or that any “good” behavior is right. There would be only behavior and desire. Of genocide, rape, betrayal of spouse and children, self deception, or even voting for the wrong party, one could only say, “I don’t like it.” Of heroism, self-effacing brilliance, truth-telling, and kindness, one could only say, “I like it.” Instead of moral truth there would be amoral preferences.

Nor could we even say that one should follow one’s own preferences when it comes to choices that involve “moral” issues. If such preferences are simply genes expressing themselves through this rather than that electrical signal, then such preferences are not moral at all. There is no “should.” And, further, there is obviously also no choice.

Even mere consistency, such as holding oneself to the same behavior one expects from others, would be an amoral preference. The golden rule would become the golden suggestion, persuasive to some, perhaps most so on aesthetic grounds–but there would be nothing binding in aesthetics any more than in “morality”–because both would be reduced to electricity in the brain, and there would be no common ground on which to stand, no common standard by which to measure anything that happens to be different about how the electricity flows in one brain as compared to another. Reason, for example, has precisely nothing to say about whether I should share my lunch with my neighbor or steal his lunch. Reason can only ever serve ends provided by something other than reason. One hopes that it serves the true, the good, and the beautiful, but it is equally adept at serving their contraries. There are inherent moral contradictions in villany (violation of the golden rule, etc.), but there is no inherent logical contradiction. Reason is silent as to what duties are owed to others.

There would, of course, remain a valid distinction between the electricity in the brain and the experience that such electricity creates. Consciousness would still be different from the underlying electrochemical events that give rise to it–but if, for every state of consciousness, there is a true one-to-one correspondence between X state of consciousness and X state of the brain, with no remainder on at least the consciousness side of the equation, then this distinction would have no consequence for “morality,” nor, probably, for philosophy. There would be, in all the wide universe, only the brain signal and the experience of the brain signal. Nothing in all 93 billion light years and counting could give rise to any escape from the thirteen-hundred cubic centimeters of the brain. And thus, in the remainder of this essay, the word “brain” will suffice to describe the brain/consciousness duality.

Even the pain/pleasure dichotomy or the avoidance of suffering could provide no foundation for moral judgments for the crude materialist. The mere fact that most people’s desires happen to concur with regard to pain and pleasure–that in general more of the one and less of the other is desirable for both self and others–could be considered only a happy coincidence. But I read in Empire of the Summer Moon that positive enjoyment of torturing captured enemies was a more or less universal feature of Native American culture. (I expect that claim overstates the facts, but I defer to the experts.) Regardless, I am certain that enjoying the suffering of others–and affirmatively seeking such enjoyment–is a real aspect of human nature in many people. No condemnation of the expression of this aspect of our nature is possible except by appeal to the notion of right/wrong or good/bad, which are (according to crude materialism) illusions of the brain. Nothing can possibly stand in judgment above the brain’s desires, because the brain’s desires are all that there is.

This constitutes a certain sort of ethical solipsism (the belief that nothing exists outside the self), because another brain inhabits a position radically distant and radically alien from the perspective of the “I-brain.” The same brain that posits the “I” may or may not happen to posit one or more “Thous” also, but this would be solely the affair of the sole “I.” The brain’s “decision,” to speak in traditional terms, to invest some other entity with the property of dignity could only be dictated, ultimately, by the I-brain’s own desires (with “desire” being, in this context, a word for certain brain states that precede certain motions in the brain that bring about certain related brain states in certain ways, as experienced within consciousness). The “Other” would, in fact, be an illusion radically different from but neither better nor truer than the illusion of “Self.” The “Other” would reduce to an expression of or a threat to the desires of the “Self.” And both would be really only an aspect of a given set of brain states, which in turn would be really only the expression of genes, themselves determined in advance by the first randomly existing set of genes and, before that, the preexisting and predetermined movements of matter–and all of it as meaningless and as void of any moral orientation as the movements of discrete atoms within a random explosion in space–which, indeed, is a simplified word picture for the big bang theory.

That it is intolerable to accept this as true would be only a very weak argument against it–but in fact it is not only intolerable but actually impossible to do so without contradiction. There are at least two contradictions that arise as soon as one attempts to accept as true crude materialism. First, if this is true, then there is no truth. Second, even if there were still a meaningful way to talk about “truth,” truth would be no better than falsehood, so “accept as true” would lose its meaning. And, aside from these internal, intellectual inconsistencies, it is impossible to think and act as if this were true.

If crude materialism were “true,” then there would be no “truth.” The concept of truth belongs to the world of ideas, and if every idea is really only an aspect of a particular set of brain states, then it defies the available assets of this system of thought to give any significant meaning to the word. There might at most be a sort semi-accidental and difficult to verify correspondence between an idea that a particular brain is generating and some aspect of “reality”–whatever “reality” would mean. In some ways, this would conduce to an admirable epistemological modesty, but this notion of a theoretical, subjective, semi-accidental correspondence between an idea generated by one’s brain and the great outer world (or the brain itself, for that matter) is so impoverished a concept of “truth” as to demand a different term. Any correspondence would be “semi-accidental” because, on this theory, the tools with which evolution has inadvertently furnished the brain are calibrated not to truth but to reproduction. To be clear, the only possible correspondence would be between matter in motion “in the world” (including in the brain itself) and a brain-generated model of how it is in motion, because matter in motion is all that exists within this system. This fact, perhaps more than anything else, is what makes the term “truth” inappropriate–for the term “truth,” as commonly used, implies not just facticity but some degree of significance. There could be no moral truth, no aesthetic truth, no spiritual truth, and precious little philosophical truth. There could only at most be a finite set of more or less accurate models of how matter is in motion in various times and places–a soulless desert of barren hypotheses. For “hypotheses,” not “truth,” would be the proper term for these models.

If crude materialism were “true” in this limited sense, then there could be no valid basis to privilege the true over the false in any normative fashion other than by expressing one’s preference for one or the other. Thus, not only would there be no “truth” worthy of the name, but the models of how matter has moved or will move in particular times and places would not matter except to whatever extent a particular brain “cares” about them. The hypotheses might matter to a particular brain, but they do not matter in any bigger sense, because no bigger sense exists. Desire would be the only basis on which to do or think anything.

More importantly, nobody acts or even thinks as if this were “true.” Nobody stops at thinking, “I didn’t like it when I got raped.” Or, “Genocide is contrary to my behavioral preferences.” Everybody whose conscience has not been broken—and everybody who might read this essay—feels justified in attributing blame to these behaviors. And it’s not just rape and genocide: we blame jerkiness and even thoughtlessness, selfishness and even excessive sadness. And we praise their contraries. We scarcely ever go an hour without multiple moral intuitions imposing themselves on our consciousness.

I would go so far as to say that morality is a constitutive part of human consciousness, perhaps nearly as much so as the Kantian categories of time, space, and causality. While a posture of disregard towards morality is possible in a way that is not possible for the Kantian categories, it remains ever present even if neglect has rendered it irrelevant and invisible as an over-familiar wall painting by the front door–or, to borrow an image from Gatsby, as eyes on a faded street poster in New York City.

Of course, just because we experience a thing as real does not mean it is actually real, nor does it mean it has any reality independent of us. Morality could be, as materialism must in all consistency suppose, a reproduction-promoting illusion. But there is something deep within us that turns, not only with loathing, but with strong intellectual rejection, from the notion that any sense of moral duty or higher purpose is a mere phantasm of the brain, that Hitler and Gandhi are actually equally non-good and non-evil. Many who become persuaded this is so commit suicide as the only meaningful decision. Better not to exist than to exist in a purposeless amoral universe with only a brain’s gene-determined desires to give direction to thought and action! But really we have no reason to categorically reject the testimony of our consciences any more than to categorically reject the testimony of our tastebuds.

The psychologist, rightly, feels an obligation to treat the sadist and the masochist even though they fulfill each other’s desires. Recognizing that good and evil are non-scientific terms, the psychologist speaks in terms of normality or functionality or prosociality. But it will not do! This linguistic substitution is helpful to my argument insofar as it shows a recognition of the amoral nature of all that comes within the proper ambit of science, but it is still either disingenuous or confused to pretend that normality or functionality or sociality are normative in themselves, such that they should be allowed to trump someone else’s desire, without first receiving an infusion from morality, open or clandestine. One must, in the end, decide that functionality, normality, and/or sociality is good, or there would be no license to attempt to “correct” the predilections of the sadist and the masochist. Without this infusion of morality, or of value judgements more broadly, treatment would take on the cast of mere domination—of imposing one’s desires or the desires of one’s society on one’s patient.

Likewise, the “justice” system would be even more of a misnomer than it already is. Currently, it at least attempts to meet out punishments whose severity is calibrated to the degree of blameworthiness attributed to the criminal behavior. Under a regime of crude materialism, there is no place for the concepts of justice or blameworthiness, and punishment would reduce to domination pure and simple–the imposition of the will of the powerful on those too weak to resist it.

It feels entirely absurd to claim that it is no better, morally, to devote oneself to the wife of one’s youth as her caregiver during her premature final illness than to divorce her and move on to other less burdensome relationships—or to kill her for that matter (and let us assume that she does not wish to be divorced or to die). And it is! I believe that refusing any moral distinction in this case is no less absurd than claiming that two plus two equals three or that a dropped ball will fly upwards.

Yet if one admits of even a single properly moral distinction—if one allows, in any context, the entry into the scene of even the smallest undesired “should”—then one must also concede that something beyond matter in motion exists. For it is just as absurd to suppose that atoms bonking into each other or holding together in any possible configuration could ever, in all of time and space, exert any moral demand. No combination of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, etc., will ever equal right or wrong, any more than any combination of piano notes could ever add up to a hamburger.

To return to Haidt, I found the following statement about his presentations to religious groups in a lovely article on The Trinity Forum:

“I’m always up front that I’m an atheist,” he explained, “but I say to them: I agree with you that there is a God-shaped hole in everyone’s heart.” That line reflects the sentiments expressed by Saint Augustine, and Blaise Pascal in his Pensées. “You and I disagree on how it got there. I’m a naturalist; I believe that we evolved to be religious. A part of being human is believing in gods and worshipping and having a sense of the sacred. And I think we have a need, we have a hole in our heart, I believe it got there by evolution, it got there naturally, and it is effectively filled by God for most people. It can be filled by other things. But I think it needs to be filled by something—and if you leave it empty [people] don’t just feel an emptiness. A society that has no sense of the sacred is one in which you’ll have a lot of anomie, normlessness, loneliness, hopelessness.”

Jonathan Haidt Is Trying to Heal America’s Divisions

It is clear, both from this quote and from various passages of The Righteous Mind that Haidt believes in the validity and correctness of certain value judgments, including certain moral judgments. Here, for example, he clearly considers anomie, normlessness, loneliness, and hopelessness to be bad things, perhaps even evils, while he accepts a sense of the sacred as a positive thing. Elsewhere in the article just quoted, Haidt refers to “moral beauty versus moral depravity,” evidently viewing these phrases as legitimate terms that refer to something real. Yet at the same time he accepts evolution as the sole and sufficient explanation for the spiritual and moral universes that we are perpetually interacting with. And my point in this essay is that evolution cannot explain these universes without destroying them. If morality is merely certain gene-determined brain states, then there is no morality.

I believe Haidt is representative of the scientific community–and especially the social sciences and medicine, whose work involves the study of humanity and not just the physical world–in that he and it have not adequately dealt with this problem. They wish to have it both ways–to posit that there is some ground other than mere desire for judging human behavior and aspirations good or bad (in whatever substituted language they prefer) and yet at the same time to assume that consciousness is reducible to the brain and the brain, along with everything else, to matter in motion. But this is incoherent.

This is not to claim that the theory of evolution or the big bang theory is false—I believe they are probably true, as far as they go, based on what experts I trust have assured me is competent evidence—but they cannot go all the way. There must be something beyond the theories’ reach, something more mysterious and wonderful than the deterministic frenzy of survival and reproduction—something that is, in fact, the very condition of mystery and wonder, the escape from the desert of barren facts, the source of moral orientation and value judgments more significant than “I like” or “I dislike.” It is not necessary to explain it, and it may not be possible to do so. One need not necessarily jump to a platonic metaphysics or a divine source for morality, and there are good arguments against doing either. One need not even accept objectivity as long as one leaves open some philosophical space not wholly within the brain for morality to inhabit. But after all, our duty is not to explicate the Good, but to appreciate and obey it. The first and most important question is not what it is in itself, but what it demands of me today.